by Taressa Stovall

by Taressa Stovall

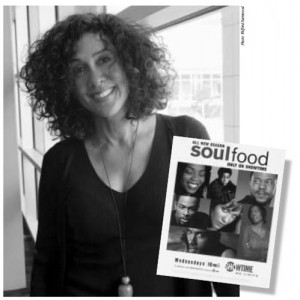

“I’m a storyteller by nature,” says Kathleen McGhee-Anderson, C’72, whose career has taken her from an English major/math minor at Spelman to serving as executive producer/writer in the fifth and final season of Soul Food, television’s longest-running African American drama.

After graduating cum laude from Spelman (where she earned her stripes onstage in the Spelman-Morehouse Players), she received an MFA in film directing from Columbia University’s School of Fine Arts, then worked as a film editor for ABC in Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles, cutting news and documentaries. She also taught film at Howard University.

The Detroit native wanted to work in the Industry, but wasn’t sure how to break in. After marrying actor/singer Carl Anderson (best known for his long-running definitive portrayal of Judas in the musical stage sensation “Jesus Christ, Superstar”), McGhee-Anderson moved to Los Angeles.

“I was still trying to figure out how to break into film,” she says. “The film and television industries didn’t overlap then as they do now.” In 1979, “the business was opening up to minority writers” and she was accepted into the Warner Brothers Minority Writers Workshop in 1979, where she learned to write for both television and film. Wanting to help create opportunities for her talented husband, she created a script for Little House on the Prairie that included a part for him. “Someone gave the script to Michael Landon [star and producer of the series], who gave me my first break. That made it easier to get other work.” Soon, she was writing for episodes of Benson, Webster, Charles in Charge, 227, Gimme a Break, and The Cosby Show.

She and Anderson divorced and with a son in high school, McGhee-Anderson opted for steadier television staff jobs, writing her own plays, feature films and long-form dramas on the side. “So many people in the Industry have to do something else while working toward their goal. The circuitous route sometimes leads to where we need to be.” Her first television staff job was with the series Amen.

She wrote a half-hour PBS show called “The Righteous Apples” and worked as supervising producer on Moe’s World, Matt Waters, South Central, 413 Hope Street and Touched by an Angel, as well as consulting producer for Any Day Now and Soul Food.

Ever focused on telling stories, she has had several screenplays and theatrical plays produced, garnering awards and acclaim along the way. Her career, she says, has been interesting, fun and challenging – but not without frustration. “The door was and is still opened wider for us as African Americans to do comedy than drama. My commitment is to try to see another quality Black drama on the air with our characters and our stories.”

Rooted in that commitment, McGhee-Anderson reflects upon the lessons she has learned working behind the scenes. “You write to become a writer, and you rewrite to become a better writer. If you want to win, you have to keep doing it. I remember once feeling very discouraged and saying to my ex-husband, Carl, that I thought I’d have achieved this or that by now. And he said, ‘you’re not dead yet.’ There’s no deadline that says you have to achieve anything by a certain date. If you’re passionate about your art, someone will appreciate it.”

Rooted in that commitment, McGhee-Anderson reflects upon the lessons she has learned working behind the scenes. “You write to become a writer, and you rewrite to become a better writer. If you want to win, you have to keep doing it. I remember once feeling very discouraged and saying to my ex-husband, Carl, that I thought I’d have achieved this or that by now. And he said, ‘you’re not dead yet.’ There’s no deadline that says you have to achieve anything by a certain date. If you’re passionate about your art, someone will appreciate it.”

She is candid about America’s obsession with fame. “What I’ve learned from being in the land of the famous is that those people who are truly at peace are past the fame. Fame is not the reward. It’s the by-product that often keeps you from doing what you want to do. With creativity, the process is the reward. You’d better love the doing of what you’re doing, because it’s not the end result that brings you the day-to-day satisfaction you need to make you happy. The end point feels good, but it’s not the hit show, the Tony, the Oscar, the commercial success. If you aren’t in love with the process, a hit show or award won’t make your life better.” In an industry built on collaboration, “you can only succeed by connecting,” she says. “You have to help others to achieve their goals and, at the same time, you’re gaining something from learning and passing on what you know. This opens you up to learning new things.” McGhee-Anderson says she keeps in touch with her Spelman sisters in the business.

She tells the story of how she had dreamt for years of a safe, pastoral place, not knowing what that place was. When she brought her son, Khalil, to his first year at Morehouse, she went to see Bessie Strong “and I looked out upon the green and it hit me that this was the scene I had dreamed of for so long without realizing what it was. It hit me that I had spent years in a safe haven and heaven here at Spelman College.”

Her Spelman experience fortified her for the battles of Tinseltown. “Spelman validated who I was as an African American woman in a world where there were no sisters doing what I do now. What Spelman told me, told us, is that we could do anything we wanted to do, that we were in the world to achieve. Our instructors encouraged and affirmed us, and that really sustained me.

“We are all important to the Spelman community you are so seen and heard – and that reinforcement gave me a launching pad that that took me through many years until I was successful. I can’t imagine having gone to a better place.”