By Mark Pattison

If we’re worker bees, how come we feel like drones so much of the time –- doing the same thing over and over, our savvy sapped from us bit by bit, our minds clouded by relentless conformity?

Kathleen McGhee-Anderson has done her share of punching the virtual time card. In the old days, we’d call it paying our dues. But now, with a couple of good scripts brought to life, she’s creating a buzz around herself.

On the surface, she’s a Black woman, so she got relegated to churning out scripts for “Black” sitcoms like “Benson,” “Webster” and “227.” But now, the Detroit-born writer seems to be breaking out of those stereotypes that had tethered her career to the taped-in-front-of-a-live-audience sitcom format. Granted, this perception may be illusory because McGhee-Anderson’s two latest endeavors reached audiences during February, Black History Month, a “feast” month in the feast-or-famine cycle of too many Blacks in the arts. Lest this sound derogatory, imagine how you’d feel seeing the fruits of your labor ripen over just 28 days a year even though you’ve toiled the other 337.

The USA cable channel actually found a night that it wasn’t presenting wrestling in prime time and showed instead her elegant made-for-TV movie, The Color of Courage – four times in February, none in March. Moreover, she put what she truly believed were the finishing touches on a stage drama that was first produced in 1985, Oak and Ivy. This bittersweet Valentine debuted in mid-February at Arena Stage in Washington, one of the capital city’s professional theater companies.

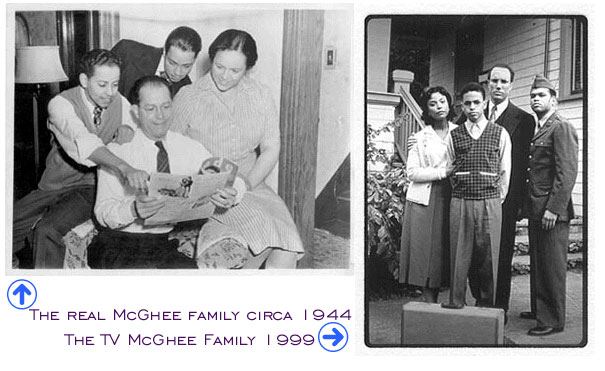

The Color of Courage tells the real-life story of McGhee-Anderson’s grandfather, Orsel “Mac” McGhee, who risked ostracism – note the last six letters in “ostracism” – to build a better life for his family.

Mac was the superintendent of building maintenance – “that’s glorified language for head janitor,” McGhee-Anderson says – at the Detroit Free Press during World War II. In the parlance of that era, he passed for White. In The Color of Courage, he was played by Roger Guenveur Smith, who, in a memorable performance in Spike Lee’s Get on the Bus, also played a biracial man who passed for White to the suspicion of a busload of Black men headed to Washington for the Million Man March.

But in Detroit circa 1944, passing for White allowed a Black person to step up, albeit at the risk of denying his own racial heritage. McGhee-Anderson remembers that her grandfather was “so White-looking” that, at Sunday dinners, “we would sit around in the dining room and look at my grandfather and marvel that he wasn’t White.”

Kathleen herself is extremely fair-skinned, and could almost pass for White, if she wanted to badly enough. Though she is “high yellow” in the jargon of African Americans who remain acutely aware of such things, her Black hair, long enough that you could call it “tresses,” has the visual texture of being, well, “Black hair.” But in our mestizo culture, you “pass” via class, not via race.

Mac’s decision to buy a house in a previously all-White neighborhood in Detroit sparked a lawsuit that barred illegal race-exclusionary covenants from home-sale contracts. They linger on in America, though, as homes get sold and resold. In tony Chevy Chase, Md., just across the border from the District of Columbia, one buyer remarked how proud he was in the early 1970s to have gotten the race-exclusionary clause stricken from his home-purchase contract.

McGhee’s lawsuit also marked the emergence of Thurgood Marshall onto the national scene; Marshall, then counsel for the NAACP, successfully argued McGhee’s case before the Supreme Court, which ruled unanimously for McGhee.

“I was really proud for him,” McGhee-Anderson says of her grandfather, in a Washington apartment furnished by Arena Stage while she redecorates the dramaturgical rooms in Oak and Ivy. “It was an important chapter in our history. In American history, really.”

In the neighborhood where one street had been the dividing line between Black and White, the seemingly simple process of moving from a house to another 10 blocks away provoked a furor The Color of Courage documented quite well.

White men of the neighborhood get a blue-collar worker from among their ranks, Ben Sipes (Bruce Greenwood), to sue on their behalf. After his wife, Anna (Linda Hamilton), defies him and continues to socialize with Mac’s wife, Minnie (Lynn Whitfield), neighbors shun her and Ben gets a taste of what it must feel like to be ostracized. He finally removes his name from the suit, which by then has taken on a life of its own.

Kathleen McGhee-Anderson

The real McGhee family circa 1944

Oak and Ivy, which tells of the rise – and fall – of the romantic and professional partnership of poets Paul Laurence Dunbar and Alice Ruth Moore, was a case of art imitating life. The play has changed since its first performance in 1985, in tandem with McGhee-Anderson’s personal changes.

When Dunbar proposed to Ruth, he said, “Marry me, and I’ll help you grow like a delicate tendril of ivy climbs the side of a sturdy oak to the sun.” For the turn of the last century, that’s about as close to a prenuptial agreement as you’re likely to find. An aspiring writer and director, McGhee married stage actor Carl Anderson, best known for portraying Judas in several touring companies of Jesus Christ Superstar. Carl was definitely further along in his career when they romanced and were wed, and the mentor mentality was in great evidence. Tired of beating her brains out in New York to further her career, McGhee-Anderson relocated to Washington, where Carl worked at Howard University, getting a teaching job herself as a film production instructor.

The two are now divorced, although still on friendly terms, primarily because of what she called “my greatest production” ever – technically, a collaboration: their son Khalil (after Indian writer Khalil Gibran of The Prophet fame), now a student at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, well within commuting distance of McGhee-Anderson’s Venice, Calif., home.

“I did not start out to write about us,” McGhee-Anderson says. But, as she matured as a writer, she discovered the parallels between her subjects’ lives and her own. “It mirrors my story.”

Oak and Ivy, despite quibbling plot contrivances, stood well on its own in its new incarnation. Other critics seemed to like the play, too, although they more than I thought it was thinly scripted. McGhee-Anderson made effective use of the Dunbars’ poems, treating them like musical numbers worthy of reprise later in the show. It didn’t hurt that they were backed up with jazz snippets composed by ex-Labelle icon Nona Hendryx and Martha Blakey, daughter of seminal jazz drummer Art.

McGhee-Anderson’s good karma continues in her role as supervising producer of the Lifetime cable channel comedy Any Day Now, about the friendship since childhood of two grown women, one White and one Black, staring Annie Potts and Lorraine Toussaint. It debuted last summer, and Lifetime executives liked it so much they ordered more episodes.

She laments the ongoing phenomenon of self-segregation, which she first recognized upon returning to Detroit during summers home from Spelman College. Her family had moved from the home of her birthplace to a racially mixed neighborhood elsewhere in Detroit in 1966. Two years later she headed for Spelman. It was 1968, the year after rioting in the city prompted one of the largest “White flight” migrations in U.S. history.

“It was so dramatically different” from one year to the next, McGhee-Anderson recalled. “I could see it more clearly than my family, who were in the midst of it,” and experiencing the change gradually.

She remembered when her father died in 1989 and her mother drove her to Detroit Metropolitan Airport so McGhee-Anderson could return home to California. Her mother wouldn’t drive on the freeways, so they drove on surface streets the entire way to the airport. “The further we got outside the city into the outlying areas, it’s like Detroit had replicated itself,” she recounted. The Detroit of yesterday she remembered so well had not disappeared; instead, “it just moved outside of Detroit. It was the same spirit, the same feeling, the same look I grew up with. It was palpable.” So too was the gasp which accompanied her recollection.

Due to White flight, Detroit grew – if that’s not an ironic word, I don’t know what is – into perhaps the most self-segregated metropolitan area in the nation. A study at the time of the 1990 census indicated that 90 percent of the Detroit area’s Whites lived outside the city, while 90 percent of its Blacks lived inside the city.

But McGhee-Anderson doesn’t sense that in Venice. The community is “extremely diverse, which is one of the reasons I’m drawn to it. There’s a melting pot on the beach.” She likes the fact that you can walk on the beach in Venice and feel connected to most people in the town, finding “a spirit of helping to maintain the area, and a pride.”

In detailing what others can do to make their own communities better, McGhee-Anderson reflected on the nature of the craft on which she embarked in 1972, when she interned in the newsroom of the same newspaper her grandfather worked at a generation earlier.

“Communicating, even on a basic level, trying to know your neighbors. I guess that’s normal for me. Separation is not possible, once you have related to your fellow man. We all care about the same things – home, family, safety, children, worship,” she said. “But you can’t know that unless you talk to one another.”

Self-segregation is “a natural instinct to want to be around your own,” McGhee-Anderson acknowledges, adding, “I don’t think it’s the best way to live in the world we have today. We’re interdependent now. It’s for our survival. It’s for our growth.” Self-segregation may benefit some in the short term, but “we have to get along together to survive on this planet. I feel as people we can transcend beyond our externals, if we’re not too afraid to reach out, if we’re not too afraid to go beyond our familiars. What’s that Frederick Douglass said? ‘No progress without struggle.’ ”

Mark Pattison is a writer who is more than his email address but finds it’s a good place to start.